References

-

UN (2023), “Secretary-General’s video message from Antarctica”, 25 November 2023; Secretary-General's video message from Antarctica | United Nations Secretary-General

-

UNFCCC (1992), UN Framework Convention on Climate Change; conveng.pdf (unfccc.int)

-

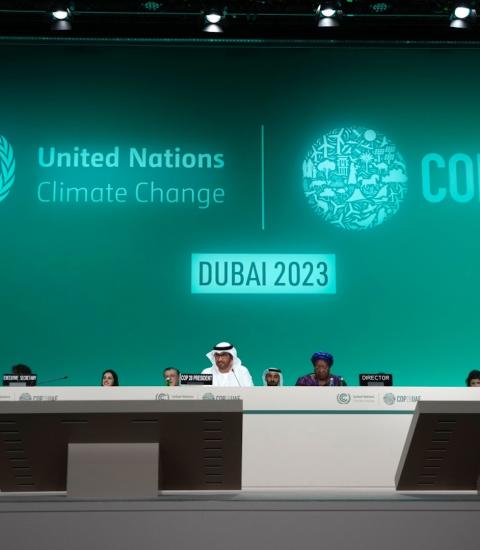

UNFCCC (1992), UN Climate Change Conference – United Arab Emirates, 30 November – 12 December 2023; UN Climate Change Conference - United Arab Emirates | UNFCCC

-

Bharat H. Desai (2022), “The Climate Change Conundrum”, Environmental Policy and Law 52 (2022) 327–328; epl219054 (iospress.com)

-

Bharat H. Desai (2023), “The 2022 Stockholm+50 Moment in the Era of a Planetary Crisis: Some Lessons for the Scholars and the Decision-makers”, Environmental Policy and Law 53 (2023) 3–18; epl219055 (iospress.com); Bharat H. Desai (2023), “ The Sleepwalking into a Planetary Crisis: Invoking International law”, SIS Blog, March 29, 2023, The Sleepwalking into a Planetary Crisis: Invoking International law (sisblogjnu.wixsite.com); Bharat H. Desai (2023), “Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-Up Call for the Decision-makers”, Green Diplomacy, February 14, 2023, Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-Up Call for the Decision-makers — Green Diplomacy; Bharat H. Desai (2022), “Regulating Global Climate Change: From Common Concern to Planetary Concern”, Environmental Policy and Law 52 (2022) 331–347, epl219050 (iospress.com).

-

UN (2022), “Secretary-General’s remarks to Stockholm+50 international meeting”, June 02, 2022; Secretary-General's remarks to Stockholm+50 international meeting | United Nations Secretary-General

-

UN (2023), “’Stop the madness of climate change, the UN chief declares”, October 30, 2023; ‘Stop the madness’ of climate change, UN chief declares | UN News

-

UN (2023), “Secretary-General’s video message from Antarctica”, November 25, 2023; Secretary-General's video message from Antarctica | United Nations Secretary-General

-

Bharat H. Desai (2004), Institutionalizing international Environmental Law. Ardsley, New York: Transnational Publishers; Institutionalizing International Environmental Law (researchgate.net)

-

Bharat H. Desai (2010, 2013), Multilateral Environmental Agreements: Legal Status of the Secretariats. New York: Cambridge University Press; crio.pdf (cambridge.org)

-

UNFCCC (1992), The Kyoto Protocol; Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. | UNFCCC

-

UNFCCC (2015), Paris Agreement; Paris Agreement English (unfccc.int)

-

IPCC (2023), Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policy Makers; IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf

-

UNFCCC (2022), “What is the Triple Planetary Crisis?”, April 13, 2022; What is the Triple Planetary Crisis? | UNFCCC

-

UNEP (2022), The Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window; Emissions Gap Report 2022 (unep.org)

-

UAE (2023), COP28, November 30-December 12, 2023; COP28 UAE - United Nations Climate Change Conference

-

UNFCCC (2022), Sharm el-Sheikh Climate Change Conference, November 6-December 20, 2022; Sharm el-Sheikh Climate Change Conference - November 2022 | UNFCCC

-

UNFCCC (2023), Why the Global Stock take is Important for Climate Action this Decade; Why the Global Stock take is Important for Climate Action this Decade | UNFCCC

-

UNFCCC (2018), Report of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement on the third part of its first session, held in Katowice from 2 to 15 December 2018. Addendum 2. Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement; Decision 19/CMA.1 (2018); Report of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement on the third part of its first session, held in Katowice from 2 to 15 December 2018. Addendum 2. Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement | UNFCCC

-

UNEP (2023), The Emissions Gap report 2023: Broken Record; Emissions Gap Report 2023 | UNEP - UN Environment Programme

-

UNFCCC (1992), n.2, CBDR&RC; Preambular para 7 and Principle 3.1 of UNFCCC

-

Ibid, Preambular para 3

-

UNFCCC (2015), n.12, Article 3, Paris Agreement

-

UNFCCC (1992), n.2, Preambular para 4

-

UNFCCC (1992), n.2, Article 3.1

-

Ibid, Article 4.7

-

UN (2023), Request for an advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice on the obligations of States in respect of climate change; General Assembly resolution 77/276 of March 29, 2023; N2309452.pdf (un.org); resolution 77/276 of March 29, 2023

-

UN (1988), Protection of global climate for present and future generations of mankind; General Assembly resolution 43/53 of December 8, 1988; Protection of global climate for present and future generations of mankind : (un.org); resolution 43/53 of December 08, 1988

-

Bharat H. Desai (2022), “Regulating Global Climate Change: From Common Concern to Planetary Concern”, Environmental Policy and Law 52 (2022) 331–347, epl219050 (iospress.com)

-

PM India (2023), Indian Prime Minister’s address at COP-28 Presidency’s Session on Transforming Climate Finance, 01 December 2023; PM participates in the COP-28 Presidency’s Session on Transforming Climate Finance | Prime Minister of India (pmindia.gov.in)

-

EPL (2022), Special Issue on Climate Change, vol.53 (5-6), Environmental Policy and Law - Volume 52, issue 5-6 - Journals - IOS Press

-

Bharat H. Desai (2023), Regulating Global Climate Change: From Common Concern to Planetary Concern. Amsterdam: IOS Press; Regulating Global Climate Change | IOS Press

-

EPL (2023), EPL Supports COP28; EPL Supports COP28 | Environmental Policy and Law

-

EPL Webinar (2023), Averting the Climate Change Catastrophe: Dubai COP28 and Beyond, December 10, 2023; Averting the Climate Change Catastrophe: Dubai COP28 and Beyond | Environmental Policy and Law