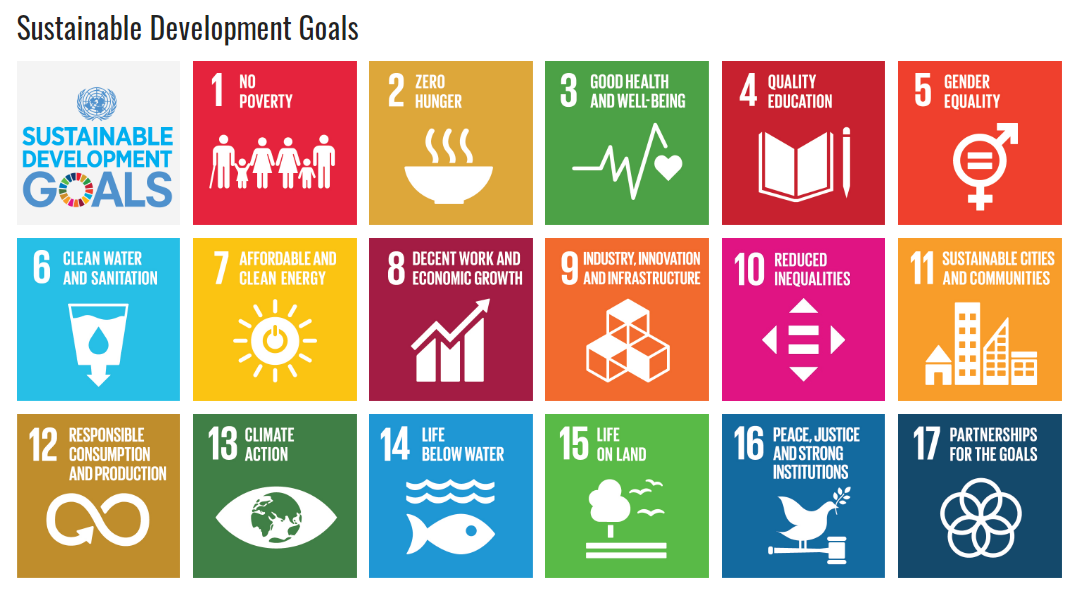

Too often, the policy domains of agriculture, energy, environment and finance (all mentioned in the SDGs) are treated separately. Effective policy-making, however, requires that institutions move beyond simple checklists and study further consequences. For example, while expanding agriculture may lead to robust food production, it may also degrade cultural and natural elements. Thus, a study of the interconnections among SDGs is very important.

Kumar et al. highlighted the importance of developing a hierarchical model as a tool to assist in policy making with regard to specific SDGs, especially in the least developed countries [3]. In addition, there are some key questions that need to be addressed when considering the sustainability of an existing system. Among these are the following (for each system):

- What system is to be protected?

- Where is the system boundary?

- What timescale should apply?

- What level of system quality needs to be maintained or improved?

Indicators are needed simply to answer the most basic operational question: “How will we know objectively whether things are getting better or worse”. Joshi et al. suggested the use of a long-term dynamic modelling system [1]; however, that study did not take all of the SDGs into consideration. Costanza et al. developed an approach that clarifies the relationship between SDGs [4]. This modelling approach is used as a sustainable wellbeing index that explores economic, environmental and social contributions, and uses a hybrid approach that integrates this index with the SDGs to determine future policy scenarios.

During their development, it was noted that the process of formulating SDGs should be based on three considerations [5]:

- The need to embrace an integrated social-ecological system perspective;

- The importance of addressing trade-offs between the ambition of goals and the feasibility in reaching them; and

- The need to be guided by existing knowledge about the principles, dynamics and constraints of social change processes, domestically as well as globally.

Following their adoption, scholars have gone on to suggest that, in order to achieve the SDGs, policy makers as well as scientists must clarify how goals and targets interconnect [6].

It is also necessary to consider the relationship between the extreme vulnerability of nature and national environmental performance. Eisenstadt et al. compared environmental performances across the globe to address why some countries seem to be more “green” than others [7]. Payne suggested that public opinion and the free flow of information promote the creation of environmental advocacy groups which in turn encourage environmental legislation [8]. This does not necessarily mean that democracies show the best environmental performance, but it does suggest that more attention should be focused on the vulnerabilities that cause some countries to be more challenged by particular environmental issues.

In this connection, it is important to take international environmental treaties and conventions into consideration, especially when considering implementation by countries which view themselves as bound by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Saner et al. suggested that a thorough examination of international agreements and treaties be conducted, in order to promote the implementation of the 2030 Agenda [9]. For example, a comparison between implementation concerns regarding Agenda 21 and the 2030 Agenda, and the identification of linkages between the two could be valuable. In this process, it would be important to highlight the uncertainties that influence the process of policy making [10]. In particular, incorporating uncertainties into the policy-making process is essential for designing and implementing effective climate change and other environmental policies [11]. The current article covers all these aspects of policy framing.

Uncertainties in Environmental Policy

The first element of this analysis is the uncertainties in environmental policy-making. Puig and Bakhtiari argued that insufficient study and attention has been devoted to the need for and means by which scientists communicate the existence of uncertainty and characterize that uncertainty in the course of informing decision-makers on climate issues [10]. Given the complexity of climate change management, it is important to incorporate uncertainty into the policy-making process and the design and implementation of effective environmental policies [11].

A protocol for clearly communicating the existence and levels of uncertainties has reportedly been developed with the specific objective of promoting accurate communication between scientists and policy makers [12]. More research is needed to analyze whether and how national-level policy-making on climate change management and other environmental issues is improving as a result of improvements in this type of communication.

The Role of Nature

Another important area of consideration relates to nature’s importance to human lives. Nature’s role in one society differs from that role in another, but it is undoubtedly important to consider this question as a key determinant in assessing the alteration in national policies that will be needed in order to achieve the SDGs.

In the 1980s, Rolston identified 10 areas of value related to nature [13]:

- economic value

- life support value

- recreational value

- scientific value

- aesthetic value

- life value

- diversity and unity values

- stability and spontaneity values

- dialectical value, and

- sacramental value.

The study conducted by Anderson et al. [14] shows that there is a significant relationship between “nature’s contributions to people” and the SDGs, and that this relationship should be taken into account when formulating environmental policies. The authors argue that where policy incorporates awareness of nature’s contributions to humans, it better demonstrates its relevance to numerous aspects of environmental development. After comparing each category of nature’s contributions with the SDGs, they conclude that goals that deal with issues like education, inequalities and justice (SDGs 4, 5, 8 and 10) are least relevant in terms of nature’s contributions, whereas energy, industry, sustainable cities and climate action (SDGs 7, 9, 11 and 13) all have a clear connection with nature. Food security, poverty and responsible consumption (SDGs 1, 2, 12 and 15) are also issues that involve a clear contribution from nature (soils, pollination, habitats and food). SDG 3 was grouped with medical priorities, but also involves nature’s contribution. Water-related clusters were linked with the regulation of water quality and quantity, and are closely connected to nature with regard to challenges such as ocean acidification and life under water (SDGs 6 and 14). Even SDGs that were not expected to have an explicit relationship to nature such as SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals), reflect a linkage with nature’s contribution, if for no other reason than that these two goals have direct linkages with all of the SDGs.

Thus, after combining the results of the study, the authors suggest that it is necessary to communicate these plural perspectives of nature’s values to stakeholders and policy makers. Linking nature values with human wellbeing is important in order to develop policies. Anderson et al. highlighted the essential role of non-material contributions to human wellbeing and identified ways to create tools that are scientifically correct [14]. Developing tools using the linkages between nature’s contribution to the SDGs would not only benefit decision-making, but would also add to public knowledge. In this way, the linkage between the SDGs and the contribution of nature to humans could be established in a way that increases the understanding of all key policy stakeholders and involved governmental bodies. Wood et al. indicate that the importance of nature lies in food, water, habitats and carbon capture as well as a secondary role for water quality and regulation [15].

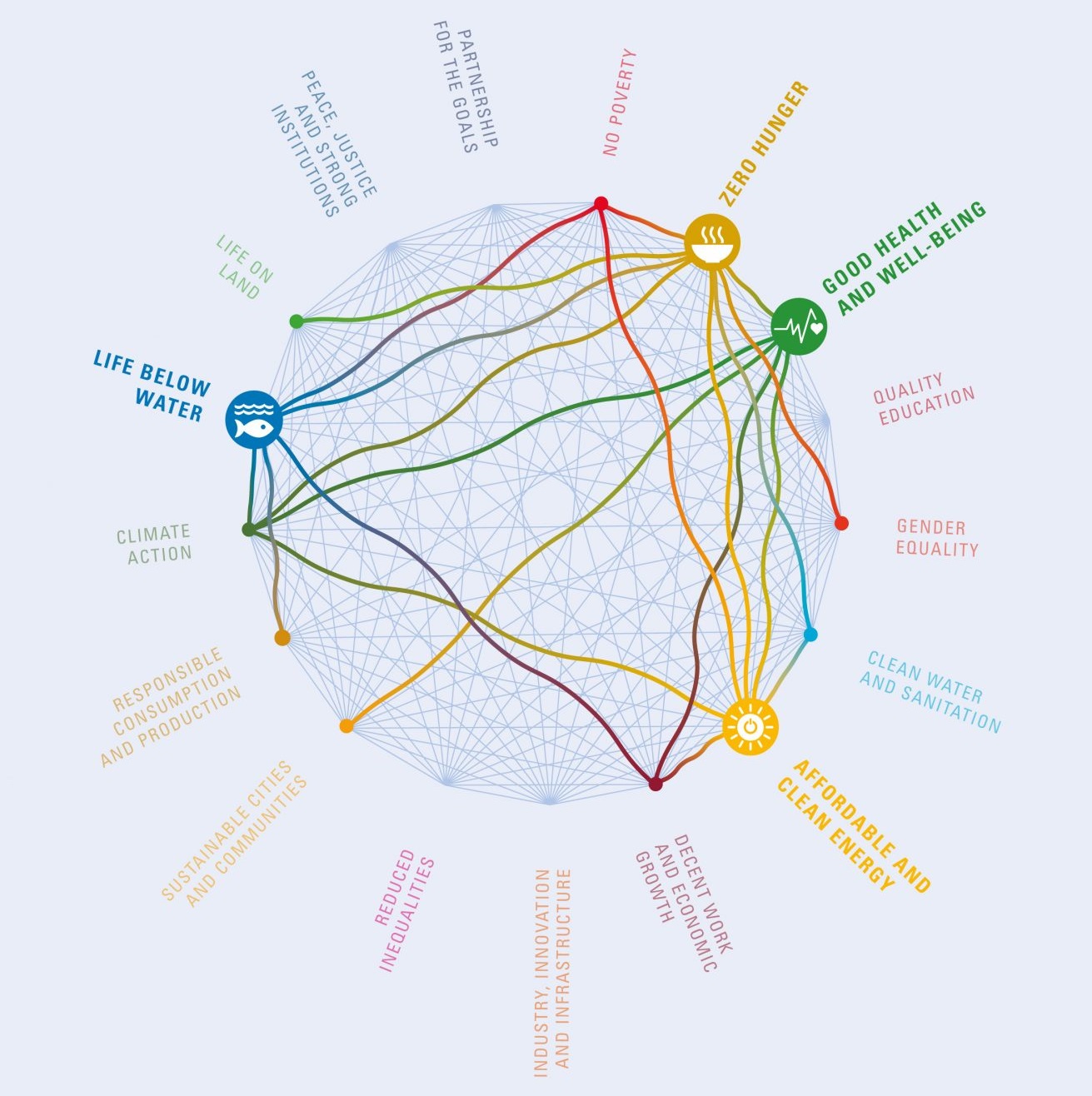

Interlinkages Among the SDGs

In order to create effective policy tools, it is essential to review the interlinkages between the SDGs, especially those that relate to environmental issues. By design, all SDGs are linked to one another, forming an integrated set of global priorities and objectives. A guide produced by the International Council for Science explores these relationships and notes that “understanding the range of positive and negative interactions among SDGs is a key to unlocking their full potential at any scale, as well as to ensuring that progress made in some areas is not made at the expense of progress in others” [16]. As shown in the study by Kumar et al., there is a significant relationship between the level of relationship between SDGs and how they complete one another.

After examining these interrelationships using interpretive structural modelling, that guide developed a structural model and a comparison of the SDGs. It identified goals with stronger correlations as “key” goals. It is important for developing and least developed countries to understand the level of interaction among the goals and how they influence one another in order to create effective policies. Le Blanc indicated that the SDGs and their associated targets can be seen as a network, in which links among the SDGs are noted through targets that explicitly refer to multiple other SDGs that were essentially made by the political process that created the goals [17]. As a result, “the political framework that the SDGs provide does not explicitly reflect the multiplicity of links that matter for policy purposes” (Le Blanc). It is essential to analyse goals and their linkages with one another in order to understand how to apply environment-related SDGs through the policy-making process.

Fredman et al. made a similar argument, suggesting that issues like gender equality are linked with multiple SDGs, and appraising the relationships between nine SDG targets [18]. They argued that particular goals cannot be fully achieved without addressing other linked goals. If a basic goal and its target are achieved, then policy makers can continue from it, going on to create policies to achieve the more general goals. General targets cannot be entirely achieved without deciding related issues.

References

1. Joshi, D.K., Hughes, B.B., and Sisk, T.D. (2015) “Improving governance for the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals: Scenario forecasting the next 50 years”. World Development 70: 286–302.

2. Dong, Y. and Hauschild, M.Z. (2017) “Indicators for Environmental Sustainability”. Procedia CIRP 61: 697–702.

3. Kumar, P., Ahmed, F., Kumar Singh, R., and Sinha, P. (2018) “Determination of hierarchical relationships among sustainable development goals using interpretive structural modeling”. Environment Development and Sustainability 20(5): 2119–2137.

4. Costanza R., Daly L., Fioramonti L., et al. (2016) “Modelling and measuring sustainable wellbeing in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals”, Ecological Economics 130: 350–355.

5. Norstrom, A.V., Dannenberg, A., McCarney, G., et al. (2014) “Three necessary conditions for establishing effective Sustainable Development Goals in the Anthropocene”. Ecology and Society 19(3).

6. Costanza R., Daly L., Fioramonti L., et al. (2016) “The UN sustainable development goals and the dynamics of well-being”, Solutions 7(1): 20–22.

7. Eisenstadt, T.A., Fiorino, D.J. and Stevens, D. 2018. “National environmental policies as shelter from the storm: specifying the relationship between extreme weather vulnerability and national environmental performance”. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 9(1): 96–107.

8. Payne, R.A. (1995) “Freedom and the environment”. Journal of Democracy 6(3): 41–55.

9. Saner, R., Saner-Yiu, L. and Kingombe, C. (2019) “The 2030 Agenda compared with six related international agreements: valuable resources for SDG implementation”. Sustainability Science 2019: 1–32.

10. Puig, D. and Bakhtiari, F. (2019) “Incorporating uncertainty in national-level climate change-mitigation policy: possible elements for a research agenda”. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 9(1): 86–8.

11. Morgan, M.G., et al. (2009) Best practice approaches for characterizing, communicating and incorporating scientific uncertainty in climate decision making. U.S. Climate Change Science Program Synthesis and Assessment Product 5.2 (Collingdale PA: Diane Publishing).

12. Fischhoff, B. and Davis, A.L. (2014) “Communicating scientific uncertainty”. PNAS 111(4): 13664–13671.

13. Rolston, H. (1981) “Values in Nature”. Environmental Ethics 3:113–128.

14. Anderson, C.B., Seixas, C.S., Barbosa, O., Fennessy, M.S., Diaz-Jose, J., and Herrera-F., B. (2018) “Determining nature’s contributions to achieve the sustainable development goals”. Sustainability Science 14: 543–547.

15. Wood, S.L.R., Jones, S.K., Johnson, J.A., et al. (2018) “Distilling the role of ecosystem services in the Sustainable Development Goals”. Ecosystem Services 29: 70–82.

16. International Council for Science. (2017) A Guide to SDG Interactions: From Science to Implementation. Available at: https://council.science/publications/a-guide-to-sdg-interactions-from-science-to-implementation.

17. Le Blanc, D. (2015) “Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets”. UN Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs, Working Paper No. 141. Available as a PDF at: https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2015/wp141_2015.pdf.

18. Fredman S., Kuosmanen J., and Campbell M. (2016) “Transformative Equality: Making the Sustainable Development Goals work for women”, Ethics & International Affairs 30(02): 177–187.

-----

The above includes extracts from the below article written by Noora Adnana Almannaei (University of Bahrain), Mohammad Salima Akhter (University of Bahrain), and Afzal Shah (University of Bahrain and Quaid-i-Azam University). To access the full article, see below.