[Author: Elizabeth A. Kirk, University of Lincoln]

Lincoln, UK – While banning single-use plastic bags is one step towards addressing global plastics pollution, more needs to be done in relation to plastic waste in our oceans. This post highlights current international law, offers recommendations, and touches on the idea of a plastic treaty – which would need to: severely limit the production of new plastic; ensure safe recycling or disposal of plastic already circulating; and provide a mechanism to clean up the plastics pollution already in the ocean. One point is clear – we need to make tackling plastics a priority.

Introduction

There are a number of international instruments which can be used or in some cases are being used to address plastics pollution in the ocean. None of the legal instruments, however, currently provide a comprehensive regime to address plastics pollution and even when combined the current plastics regime, if it can be called a regime, is focused largely on the development of understanding of the scale of the problem and on development of monitoring and assessment techniques. While there are some exceptions to this general focus, even those agreements which may go some way towards preventing, or reducing plastics pollution, are limited in their ability to do so.

Relevant Treaties and Soft Law

The most obvious treaty with which to begin any discussion on the law relating to plastics pollution is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) [1]. It sets out a number of obligations which are relevant to the control of plastics. Article 207, deals with the control of pollution from land-based activities, Article 210 the control of pollution from dumping and Article 211 the control of pollution from shipping. Given the number of parties to (UNCLOS) these provisions are almost universal in application. They are also supplemented by the customary international law obligation not to cause harm to, or allow activities within one’s jurisdiction to cause harm to other States or areas beyond national jurisdiction. The problem, however, with both the customary obligation and with the provisions of UNCLOS is that none provide detail as to precisely what measures States should take to control pollution from plastics. That detail is to be drawn from internationally agreed standards, rules, and recommended practices and procedures. These too are, however, rather limited in extent at least in so far as they address pollution from plastics. Certain aspects of plastics pollution are addressed and certain limitations placed on the disposal of plastics, but the regulation is by no means comprehensive.

Ship source plastics pollution is addressed through the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) [2] and its Annex V [3], which places a general prohibition on the disposal of garbage at sea which includes plastics such as from packaging and single use cups, plastic ropes, and fishing gear. Plastics pollution from dumping is addressed through the 1972 Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (London Convention) [4] and its 1996 Protocol (London Protocol) [5]. Again, it is addressed as part of the wider regulation of dumping rather than as an issue on its own. Work is, however, being undertaken under both MARPOL and the London Dumping regime to understand the full extent of the problem of plastics pollution and the further steps necessary to address it.

Both ship source pollution and dumping are, however, relatively minor sources of plastics pollution. The greatest source of plastics pollution is land-based activities and indeed even the plastics dumped at sea largely originate from these sources. International efforts to address plastics from land-based activities are, however, quite minimal. There is no equivalent of MARPOL or the London Dumping Convention in respect of land-based activities. While some individual pollutants are addressed through treaties, such as the Minamata Convention which addresses mercury [6], there is no plastics treaty as such.

There are some treaties which are relevant to the control of plastics pollution from land-based activities. The Basel Convention [7] regulates trade in waste and from December 2020 will treat all plastic that is not destined for recycling as hazardous [8]. The significance of this designation is that it will mean that plastic waste can no longer be exported unless there is no possibility of disposing of it safely in the State of origin. This should lead to a reduction of plastic waste being lost at sea in the course of transit, but it may not lead to an overall reduction in the volume of plastic waste entering the oceans, if it is not supported by other measures. Other treaties, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity [9], are also relevant in so far as their parties have adopted decisions relating to improving understanding of the impact of plastics on marine life, but they take us no further in terms of the actual regulation of plastics pollution. There are some more promising developments within soft law – non-binding instruments through which States agree to take action, though again, for now, that action is somewhat limited.

The Global Programme for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities [10] has acted to address plastics pollution, but at first its efforts were focused on monitoring and understanding the nature of the pollution problem. In addition, it has tended to treat plastics as part of a wider marine litter problem. It was not until the fourth inter-governmental review in 2017 that States committed to accelerate efforts to address marine pollution from plastics [11]. States agreed to “implement long-term and robust strategies to reduce the use of plastics and microplastics, particularly plastic bags and single use plastics, including by partnering with stakeholders at relevant levels to address their production, marketing and use” [12]. States also established a sub-programme on marine litter within the 2018–2022 programme of work. Once again, however, the decisions as to precisely what measures to adopt and how to implement those measures were left to States.

The United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) has also set up an open-ended expert working group on marine litter and micro-plastics [13], and called upon States and relevant intergovernmental organizations to develop understanding of the nature of plastics pollution and to take measures to address that pollution [14]. One of the interesting features of these calls is that States are often times encouraged to work with the private sector to find ways to reduce plastics pollution as they were during the fourth session of UNEA.

Commentary and Recommendations

The international regulation of plastics pollution contains significant gaps through which millions of tons of plastics continue to pour into the oceans. International measures are focused on understanding the problem and encouraging States to act without giving concrete direction on the measures to take. While many states have adopted measures such as banning single use plastic bags [15], it is clear that we are far short of the range of measures needed if we are to address plastics pollution in the ocean fully.

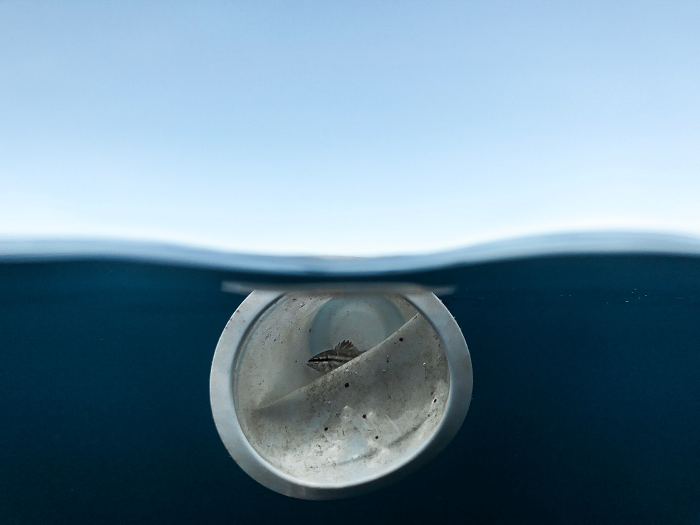

We know that plastics are causing significant problems within the environment. By now, pictures of marine species tangled in nets or dead from starvation due to their stomachs being filled with plastic, are widespread. At the same time, plastics degrade in the environment and as they do their pitted surfaces become host to viruses and toxins. As the plastic is ingested by plankton and on through the food chain to humans, the toxins can accumulate causing real health risks. There is then a real urgency in the need to address plastics pollution. Perhaps for these reasons the notion that a plastics treaty is necessary is gaining traction. Indeed, the potential need for and benefits of a new plastics treaty were discussed in the open-ended expert working group on marine litter and micro-plastics [16]. The question is what should such a treaty focus on?

In short, a plastic treaty would have to do three things – severely limit the production of new plastic; ensure safe recycling or disposal of plastic already circulating in the economy; and provide a mechanism to clean up the plastics pollution already in the ocean. The third of these requirements might in some ways be the easiest to achieve. A plastics fund could be established to cover the capture and removal of plastics from the ocean. The fund could be supported in a similar way to the Fund Convention [17], which is financed through contributions from importers and exporters of oil. A similar approach may lead to questions regarding the production and use of plastics wholly within a single State, so perhaps the net of contributors would have to be cast more widely to encompass all treaty members, not just importers and exporters.

To ensure the second element is met (safe recycling and disposal), a plastics treaty would have to facilitate sharing of technology – such as plastic-eating enzymes [18]. The investment required to ensure safe recycling of plastics would have to be significant, as only around 9% of the plastics produced since 1950 have been recycled [19]. Measures would also have to be agreed on as to what constitutes safe disposal of plastics given how long it can take for plastics to degrade naturally.

The first element (limiting production) would also require careful consideration. While there have been suggestions that moving away from oil-based plastics might be sufficient, biodegradable and plant-based plastics can be as problematic as oil-based if not disposed of properly [20]. It may therefore be that the only way to limit production is to focus on phasing out certain uses of plastic. Single-use items, such as plastic bags, will likely be the easiest to phase out. Taking plastics out of other products, such as computers, hearing aids, footwear, and intensive care ventilators, will prove much harder. Nevertheless, if we are to tackle plastics pollution, then our priority must be to identify which uses of plastics can be stopped and which are and will remain essential.

References

1. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (adopted 10 December 1982, entered into force 16 November 1994) 1833 UNTS 3.

2. International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (adopted 2 November 1973, entered into force 2 October 1983) 1340 UNTS 184.

3. Regulations for the Prevention of Pollution by Garbage from Ships (adopted 15 July 2011, entered into force 1 January 2013) IMO Res MEPC.201(62) (MARPOL Annex V).

4. Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (adopted 13 November 1972, entered into force 30 August 1975) 1046 UNTS 120 (London Convention).

5. Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, 1972 (adopted 7 November 1996, entered into force 24 March 2006) 36 ILM 1 (London Protocol).

6. Minamata Convention on Mercury (adopted 10 October 2013; entered into force 16 August 2017).

7. Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (adopted 22 March 1989, entered into force 5 May 1992) 1673 UNTS 57 (Basel Convention).

8. Revision to Annex IX introduced through Decision BC-14/13: Further actions to address plastic waste under the Basel Convention. May 2019.

9. Convention on Biological Diversity (adopted 5 June 1992, entered into force 29 December 1993) 1760 UNTS 79.

10. UNEP (1995) “Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities.” UN Doc UNEP(OCA)/LBA/IG.27 (GPA).

11. UNEP (2017) “Draft Programme of Work of the Global Programme of Action Coordination Office for the period 2018–2022 (Advance Copy).” UN Doc UNEP/GPA/IGR.4/4, para 8(g).

12. UNEP (2017) “Draft Programme of Work of the Global Programme of Action Coordination Office for the period 2018–2022” (Advance Copy) UN Doc UNEP/GPA/IGR.4/4, para 8(i).

13. UNEP/EA.3/Res.7 Marine Litter and Microplastics.

14. United Nations Environment Assembly Resolution 4/6 on Marine plastic litter and microplastics 15 March 2019 UNEP/EA.4/Res.6.

15. United Nations Environment Programme. (2018) Legal Limits on Single-Use Plastics and Microplastics: A Global Review of National Laws and Regulations. Available at: https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/publication/legal-limits-single-use-plastics-and-microplastics-global-review-national (last accessed: 18 November 2020)

16. Revised Draft Chair’s Summary For The Ad Hoc Open-Ended Expert Group On Marine Litter And Microplastics For consideration at the 4th session of the expert group, 9-13 November 2020.

17. 1992 International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage (Fund Convention). Adopted: 18 December 1971; Entered into force: 16 October 1978; superseded by 1992 Protocol: Adopted: 27 November 1992; Entered into force: 30 May 1996, UK Treaty Series No. 87 (1996) Cm 3433 Cm3432.

18. Melissae Fellett. (Feb. 28, 2018) “Improving a Plastic-Degrading Enzyme for Better PET Recycling.” Chemical and Engineering News.

19. Roland Geyer, Jenna R. Jambeck, and Kara Lavender Law. (2017) “Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made” Science Advances 3(7): e1700782.

20. Danny Taufik, Machiel J.Reinders, KarinMolenveld, and Marleen C. Onwezen. (2020) “The Paradox Between the Environmental Appeal of Bio-Based Plastic Packaging for Consumers and Their Disposal Behaviour.” Science of the Total Environment 705: 13582.